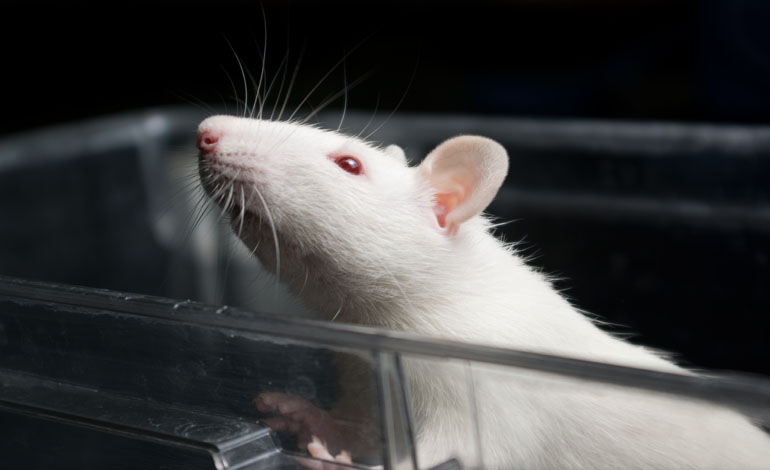

We Pawsies love animals. The thought of rabbits, monkeys or mice in laboratory cages, being administered a medication which may—or may not—one day be approved for human use makes our hearts sink. Are these types of tests still a “necessary evil”?

Every year some 3.5 million animals—mostly fish, birds and mice—are used in laboratory tests in Canada. We share approximately 80% of our genes with mice and for the time being don’t have other methods to test the efficacy of medications or vaccines which are as effective as animal testing, according to Luc-Alain Giraldeau, Chief Executive Officer of Quebec’s Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS). He’s a specialist in animal behaviour and the past president of the Canadian Council on Animal Care, the organization that sets and maintains standards for the care and use of animals in science.

“For cosmetics, on the other hand, we can obtain reliable test results from in-vitro tissue culture testing or computer simulations,” he specifies. Giraldeau reminds us that procedures have greatly improved—in part due to the Council’s strict rules which have rapidly and constantly evolved since they were first implemented in the 1970s. “Researchers must now justify their use of animals before a committee, use the smallest possible numbers required to obtain a specific result, and ensure that animals don’t suffer— by administering anesthesia, for instance. The time when 300 rabbits were administered a product sample is over.”

Unfortunately, however, only research institutes affiliated with universities and colleges are obliged to respect these rules. In the private sector—and in countries that are less respectful of animal rights—practices are more questionable.

Animals: Inferior to humans?

For many years, the outcry against biomedical testing has been grounded in the argument that animals are sentient beings, that they feel pain, as we do. Valéry Giroux, an animal ethics researcher, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law at Université de Montréal and coordinator of the Montreal-based Interuniversity Centre for Ethical Research (CRE), is one of the advocates voicing concern.

“The value of experiments on animals for human-health research is contested—even within the scientific community, because it’s often difficult to extrapolate results to humans,” says Giroux, who’s also a fellow at the Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics. “But even if a small portion of these tests is useful, does this make them justifiable?

When we ask why these tests aren’t conducted on human beings, it’s tempting to respond that it’s because human beings are worth more than animals.

We base our decision on biological (species-related) criteria and argue that animals have cognitive abilities that are inferior to those in humans, which is an argument that opens the door to dangerous discrimination. By following this line of reasoning, you could argue that experiments on people with lower IQs are justifiable …”

According to Giroux, who’s published numerous articles on animal rights, the fact that something is deemed necessary does not, by definition, make it morally acceptable. “All sentient beings have fundamental rights. We must not inflict pain on them, keep them captive or kill them. These actions are oppressive and dominating.”

Luc-Alain Giraldeau agrees that it’s a thorny issue. “It’s clear that you have to convince the public that the suffering inflicted on animals serves a purpose. I understand the ethical and philosophical controversies—and it’s important to have these discussions—but we must bring the debate back to the world in which we live: some people are terribly sick and other people want to heal them.”

There are several options on the horizon that may help reduce, or even eliminate, the use of animals in laboratory tests. The in-vitro production of human tissue (such as skin) from human cells, and artificial intelligence both show great promise. And an algorithm developed by researchers last summer proved very effective in predicting toxicity.

Let’s hope these fields continue to evolve quickly.